Jeremy Heywood was Cabinet Secretary – the UK’s most senior Civil Servant – from 2012 to 2018. He was extremely open to new ideas, and alternative perspectives. The Heywood Prize was created by the Heywood Foundation to continue that spirit of inclusivity and innovation.

This is the entry to the 2022/23 competition by Shirin Eghtesadi, which was shortlisted, but sadly did not win a prize.

The 2022/23 Heywood Prize: What do you think the government should do to improve life in the UK?

Most people go into politics to do good, to make an impact and to serve those who put their trust in them. Politicians have strong views about the role and size of the state. The right considers the state to be a barrier to creativity, entrepreneurship and individual freedom. The left considers it as the way to keep predatory businesses in check and ensure fairness in society. Feelings run high on both sides.

This submission aims to take ideology out of this debate and focus on evidence about what works best. What is the optimal size and role of the state? We hope that our submission contributes to a fact-based solution to this question.

A government that formulates policy to ensure an optimal state serves the nation by steering it towards an increase in life expectancy, in social mobility, in median income, a decrease in poverty – and an increase in happiness.

How are we doing?

Since 2010, in the UK, there has been a drive to keep the size of the state small and transfer more of its functions to individuals, private sector and charities. While most other leading economies have adjusted (upwards) the size of the state to meet the increasing needs of their populations, the UK has not (see Figure 1).

The ideological foundation of this drive to contain the size of the state is a belief in individualism and the superiority of market forces to determine outcomes. An example is the NHS 2012 Health & Care Act. The Act removed responsibility for the health of citizens from the Secretary of State for Health and replaced it with a complex system that unfortunately doesn’t work as well. In 2014 the NHS was cited by the Commonwealth Fund as the best health care system in the world; It is now struggling badly. There are many other such examples.

The consequences for the UK population have been dire: as John Burn-Murdoch pointed out in the Financial Times,

“Real wages in the UK are below where they were 18 years ago. Life expectancy has stagnated, with Britain arcing away below most other developed countries, and avoidable mortality — premature deaths that should not occur with timely and effective healthcare — rising to the highest level among its peers, other than the US whose opioid crisis renders it peerless.”

What do we need to fix?

Governments cannot be expected to fix all our ills. An attempt to do so would result in a ‘Big Brother’ state. We want to have the freedom to choose for ourselves, but we also want safety, security and not to constantly worry about our future, about things going wrong, about being left behind. Governments cannot simply wash their hands of responsibility for societal outcomes. A government presiding over a country with high rates of poverty, lack of social mobility, falling life expectancy, and high levels of dissatisfaction, polarisation and anxiety must look again to see why things are the way they are and what they can do about it.

One thing that is undisputable is that we (human beings) are not an island: whether we like it or not, our actions impact each other. Therefore, we need a structure/state to protect us from others’ potentially harmful actions. The question is not about whether to have a state, but where to draw the line. We need to find a balance that works for us.

The relationship between what needs fixing & role of the state

The world has over 200 countries and each has a different economic system. Some work better than others for their population. Some have smaller states, some have larger ones. We have explored the relationships between state size and poverty rates, social mobility, life expectancy and general happiness of a nation (see Appendix). What has emerged is that the two extreme points on the spectrum of state sizes don’t work well for the population. We will call what works an optimal state.

The drive for ‘individualism’ has not delivered the goods it once promised. As inconvenient it may be, it looks as though our experimentation with individualism needs a review. Doubling-down and continuing blindly would produce ever-worse outcomes for the UK population.

Optimal state

The role of the state is to formulate policy and to take actions that benefit the population as a whole – an optimal state is one which does this as well as possible. We define ‘size’ of the state as Government revenue as % of GDP. In a country where most economic activity is private enterprises, that percentage of GDP would be lower than in a country where there were more nationalised institutions. There is, of course, more to being an optimal state than simply being the optimal size; but it is impossible to be an optimal state without being the optimal size.

If we consider high social mobility, low poverty rates, high median income, high life expectancy as desirable outcomes for our population, then we should be curious to see if the drive to shrink the state is the way to go.

The World Happiness Report publishes yearly league tables of countries and their populations’ reported happiness. Unsurprisingly, there is a correlation between high social mobility, low poverty rates and high life expectancy and happiness (see Appendix). Less obviously, there is a correlation between the size of the state and happiness of the population. Almost all the countries on the high end of the happiness spectrum reside somewhere in the middle of state size spectrum (state size being 40%-55% of GDP).

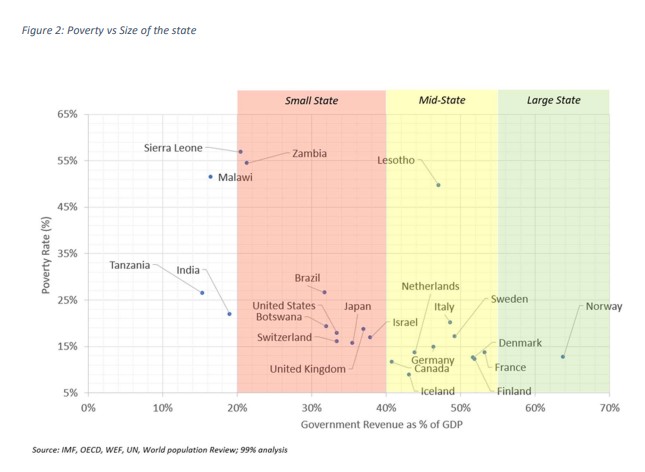

To understand this better, we looked at poverty rates and state size (see Figure 2). The data indicate that it is not possible to have a low poverty rate (<15%) in a small state (less than 40% GDP). There is also a correlation between lower poverty rates and happiness. In countries where poverty rates are lower, general happiness of the population is higher.

Another desirable outcome for a country is high life expectancy. As expected, the data show a strong correlation between life expectancy and general happiness of the population. And again, small states deliver lower life expectancy.

Social mobility is another favourable outcome. We all want to believe that our aspirations can be realised, if we set our minds to achieving them. The evidence indicates that social mobility is lower in smaller states (see Figure 3). This runs counter to the story we were led to believe, that the market forces will lead us into a world where with talent and hard work everything is possible.

The evidence is not in favour of small states. Trying to keep the state small – and even to shrink it further – was not such a good idea; and continuing to do so would be highly irresponsible.

There is not such reliable (or plentiful) data on large states – the really large ones, like North Korea do not provide accurate statistics – nevertheless, it is a reasonable hypothesis that too large a state would also be sub-optimal. This is not an issue for the UK at the moment, however, as all the evidence suggests that our state is below the optimal size, not above it.

What should the government do?

The government should:

- Instruct the Cabinet office to set up a project to:

- Define Key Performance Indicators for a successful state that serves its population well

- Benchmark performance of UK against other countries

- Identify best practice and key factors in terms of size and role of state in driving high performance

- Support other government departments to define and implement a migration strategy towards optimal performance

- Instruct Treasury to define a funding strategy for an optimal state

Conclusion: Make the UK an optimal state

The experimentation with individualism was perhaps a brave one. No one set out to destroy the world. But after 40+ years, evidence shows that the experiment has failed. And we are polarised, poorer, anxious and weary. What do we do? Do we double down? Do we blame and point the finger at each other? Or do we take a breath, look again and work together to build back better?

In this submission, we invite policymakers and their advisers to look at the evidence and explicitly target transforming the UK into an optimal state. This means benchmarking the performance of the UK against the world’s best performers in terms of low poverty rates, high social mobility and life expectancy, understanding the policies and actions their governments have put in place and learning from what works – as it would be termed in business circles: identifying and adopting best practice.

There is a wealth of talent in this country. By focussing on the idea of building an optimal state, we can learn from what works and build back better.

If you think these proposals deserve wider circulation, please share using the buttons below this article.