This article was written by 99% members Norma Cohen and Mark E Thomas in response to a question posed by the FT as part of the 2021 Political Essay Competition. Their entry did not win.

Norma is the FT’s former demography correspondent and author of a PhD thesis, How Britain Paid for War: Bond Holders and the Financing of the Great War 1914-32.

Question: With UK real income per head up 15 times over the past 200 years and more evenly distributed, will this be repeated over the next 200 years? – and if not, why not?

Introduction

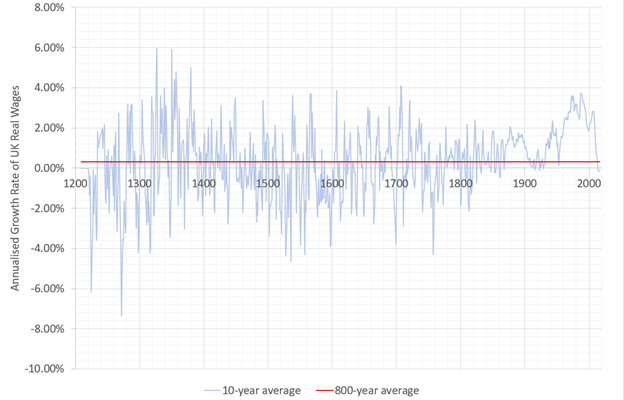

Britain’s wealth today would have been unthinkable 200 years ago, and that wealth is distributed more widely than could have been imagined. But those 200 years have been anomalous: there is nothing comparable in the last 800.

Figure 1: 800 Years of Real Wage Changes

Source: Bank of England[1]

And this 200-year progress and its benefits have neither been distributed uniformly over time nor across the population.

In assessing whether this anomalous, patchy progress can continue for the next 200 years, we must look at how we got here, starting with the Industrial Revolution. By looking at what drove the past, we can make some conjectures about the future.

Specifically, we see that the principal determinants of economic progress and its beneficiaries have been four factors: technology; war; crises caused by ‘external’ shocks; and the economic system (underlying philosophy, institutions, and policies).

Considering these factors suggests both that we should aim to deliver another 15-fold increase in living standards and that this will require radical changes in our mindset and policies.

The last 200 years

The Industrial Revolution (1800-1880)

The revolution started around 1750, but its effects became material around 1800.[2] It marked the first time that economic growth was driven more by technology than by economic policies.

Its inventions – from the steam engine to the spinning jenny – allowed Britain to build industrial capacity before any other country. By 1851, Britain was the world’s undisputed economic leader.[3] But wages did not benefit immediately: there was a 30-year plateau.[4]

The Belle Epoque (1880-1914)

The upper classes enjoyed unprecedented luxury, but poverty remained widespread. Around 30% of men aged 65+ were on Poor Relief.[5] Even by the early 1900s, many of the ‘respectable poor’ lived on wages of around a pound a week (equivalent to household income ~£126 a week today[6]) and mortality of young children ran at ~20%.[7]

Wealth during the Edwardian years was highly concentrated: 1% of the population owned ~70% of the national wealth, making Britain more unequal than most other European countries.[8]

The First World War (1914-18)

In 1914, Britain remained hugely unequal: almost 70% of the wealth was still held by the top 1%, with the bottom 99% sharing the remaining 30%.[9]

The war revealed the failure to invest in human capital: of 2.5 million men examined by the National Service Medical Boards in 1917-18, only 36% were fit for full military duties. In some industrial areas, ~70% were unfit for overseas duties.[10]

The Interwar years (1918-39)

After a brief boom following Armistice, a crushing depression set in. From 1921-1929, unemployment never fell below 10%; in the global slump of the 1930s, it rose to over 20%.[11]

The Second World War (1939-45)

The demands of war for military workers soaked up excess labour supply. But the bitter memories of interwar years held. Sir Ernest Bevin, accompanying Churchill to see British troops off for D-Day, recalled one soldier’s challenge: ‘Ernie, when we have done this job for you, are we going back on the dole?’[12]

The Golden Age of Capitalism (1945-1980)

After 1945, many countries needed to rebuild. For most, that rebuilding required embracing previously excluded groups. Many experienced an economic miracle. In the US and the UK, we saw the Golden Age of Capitalism.

There is debate about the duration of this Golden Age because of the crises of the 1970s. I have taken the period 1945-1980 because the economic system remained essentially the same throughout. In the same way, I have credited the results of the Global Financial Crisis to the Age of Market Capitalism which I take as 1980-2020.

Lord Skidelsky describes the Golden Age as a time where the dominant economic system was Keynesian, with governments taking responsibility for maintaining high employment and cooperating to build a new international order including the Bretton Woods system.[13] This period saw governments funding infrastructure projects, creating social security systems and healthcare systems, and investing in education for their populations.[14]

This system worked unprecedentedly well until the early 1970s.

The 1970’s saw the collapse of the Bretton Woods currency exchange system and two oil price shocks. The resulting dislocations in the UK, the US, and elsewhere set off spiralling inflation which, in turn, created political shockwaves.

There was an appetite for change.

The Age of Market Capitalism (1980-2020)

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected UK Prime Minister; and in 1981, Ronald Reagan became US President. These two leaders brought a new form of capitalism – Market Capitalism.

Skidelsky writes:

“… by the 1980s both theory and policy had swung back to pre-Keynesian ideas. Government was seen once more as part of the problem, not the solution.” [15]

Market Capitalism was codified in the 10 points of the ‘Washington consensus,’ which described the standard economic reform package recommended by Washington-based institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.[16] These 10 principles are the basis of what was meant by ‘reform’ of the economy. They have two main thrusts: to free up the private sector and to shrink the role of the state.

Like the Golden Age, the Age of Market Capitalism has seen crises, of which the most recent, and until last year the most serious, was the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) which reached its crisis point in September 2008.

The recession after the GFC – exacerbated by the austerity which many countries adopted as their response to the crisis – has been dubbed ‘the Great Recession.’[17] Many countries’ populations (including the UK’s) are poorer today than they were in 2007.[18]

On most measures, the results were far better during the Golden Age of Capitalism.

Figure 2: Comparison of Golden Age with Market Capitalism

Sources: See text below

Overall growth was higher;[19],[20] growth per capita was higher;[21],[22] median household income grew faster;[23],[24],[25] and unemployment was lower.[26],[27] The only measure on which Market Capitalism performed better was control of inflation.[28],[29]

We have had two post-war periods with two different economic systems; the Golden Age performed better, but both saw crises. The crises at the end of the Golden Age brought radical change and ushered in Market Capitalism; the crises at the end of the Age of Market Capitalism have not brought comparable change.

The last 200 years have seen remarkable progress, and we are vastly better off because of it. But to suggest that there has been anything resembling smooth, consistent progress over this time would be false.

The four factors identified in the introduction – crises, technology, wars, and the economic system – have all shaped the rate of progress (and regress) at different times.

The Next 200 years

When we consider whether the next 200 years will see another 15-fold improvement in living standards, we can think arithmetically, or in terms of those four factors.

Arithmetically, the challenge does not seem demanding. Assuming that the benefits of growth were shared throughout the population, a compound annual real wage growth rate of 1.36% would produce another 15-fold increase in living standards. Both the US and the UK exceeded that figure during the Golden Age.

But when we think about how the four factors may interact, the challenge becomes more daunting. As the American sociobiologist E. O. Wilson put it, “The real problem of humanity is the following: we have Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technology.” [30]

The interplay between our institutions, our emotions and our technology will be even more difficult to manage over the next two centuries than it has been over the last. And the UK cannot ignore the rest of the world – any global crisis will prevent us replicating the success of the last 200 years.

Crises

To prevent a civilization-ending crisis or even human extinction, Cambridge University established a Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.[31] Its five major concerns are: biological risks (pandemics); global justice; extreme technology; artificial intelligence (AI) and the environment. This essay can cover only the environment and AI.

On the environment, the World Bank estimates that, globally, climate change could plunge as many as 122 million (additional) people into extreme poverty.[32] But this may be conservative: without significant policy change, the UN says, we could be looking at temperature rises of over 3°C – more serious than the World Bank scenarios.[33] Food prices could rise by up to 20%.[34]

The direct effects in the UK may be less severe than in some other countries,[35] but it would be courageous to assume that we could remain immune to the global stresses and their responses up to and possibly including war: “Armed conflict between nations over resources… is likely and nuclear war is possible.”[36]

Technology

The developments we can expect in the next few decades are mind-boggling. Nanotechnology will advance in areas from genetic editing through to new materials like graphene; renewable energies will become widely available – possibly even nuclear fusion; and computing power will explode both with the advent of quantum computing and, most fundamentally, artificial intelligence (AI).[37]

These technologies are unimaginably powerful (literally so in the case of AI once the ‘singularity’ – the point at which machines become more intelligent than humans – is passed).

As a force for good, this power is tremendous. It is as great as a force for ill.

War

The outcome of war is increasingly driven by technology: WW I killed around 0.5% of the world’s population;[38] WW II killed almost 3.5%.[39] WW III would almost certainly kill far more, and many scientists believe that it would trigger the end of our current civilisation.

As Albert Einstein commented, “I know not with what weapons WW III will be fought, but WW IV will be fought with sticks and stones.” [40]

To deliver another 15-fold increase in general living standards over the next 200 years, we must avoid another major war.

Economic System

So far, our crisis response has not replaced Market Capitalism: we have effectively doubled-down on the bet that ever-smaller states and ever-freer markets will solve our problems. There is no evidence, however, of Market Capitalism ‘working’ except as a way of containing inflation. And it is not clear that it is compatible with tackling the climate crisis.

Furthermore, it is doubtful that Market Capitalism is a stable system, capable of running for the next 200 years, even if none of the other factors cause problems. Global imbalances, private debt levels and their consequences for inequality and the stability of the financial system could all produce too great an internal strain. [41]

Attempting to persevere with Market Capitalism would make another 15-fold rise in living standards impossible.

To achieve progress over the next 200 years comparable to the last 200 will require judicious management of all four factors. Before the singularity, it will be human decision-making which determines how well we manage these challenges; after the singularity, it will – increasingly – not be.

Even the experts cannot be sure when (or whether) the singularity will take place. But the median opinion of AI researchers is that it will take place before the year 2050.[42] Beyond that point, by definition, artificial intelligence will be more powerful than human intelligence.

This means we need prophylaxis. Many people have pointed out the dangers.[43] As the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk writes: “Our current systems often go wrong in unpredictable ways. Aligning current systems’ behaviour with our goals has proved difficult and has resulted in unpredictable negative outcomes. Accidents caused by more powerful systems would be far more destructive.” [44]

Pre-singularity (2020-2050)

To sustain progress, we need to change the economic system from Market Capitalism to one which focuses on the needs of the population and of the scale of the climate emergency. There are many variants of the kind of ‘Green New Deal’ thinking which will be necessary.[45] In addition there are fundamental constitutional and governance issues which must be tackled in order to sustain the new policy directions.[46] And we must tackle the problem of corporate externalisation of costs – aligning the profit motive with the progress we need to see.[47]

With these changes to the economic system, we can begin to make the kinds of investments needed to stimulate good (environmentally friendly) growth in the economy, and to share that growth fairly.

Recent years have weakened the international order.[48] To succeed, we must help rebuild it: strengthening ties and rebuilding international institutions. The UK acting alone cannot have a material effect on the first three factors – crises, wars, and technology: we need to think and act globally and support others in doing so.

And, assuming we avoid crises, we must think more seriously about technology.

As Sohn wrote:

“Horses were used extensively …in 18th and 19th century America and Europe, but once mechanisation and electrification were implemented… the horse population declined quickly and dramatically. The same can probably be said about humans in the 21st century: we just don’t need that many of them”[49]

There will be a complex interaction between the aging of the population and automation, but it is increasingly clear that an economic system in which having a decent life depends on having a decently-paid job, the prospects for rising living standards risk becoming remote.[50] We need a new social contract fit for an increasingly automated world.

The experts are aware of these risks and treat them seriously – our politicians currently do not.

Post singularity (2050-2120)

On the (critical) assumption that we navigate the next 30 years to avoid crises and produce green, fair growth in the economy, and that we align the power of AI with our goals, the period from 2050-2120 will see extraordinary progress.

We will have a strong, fair economy with clean energy, clean industry and clean agriculture. And we will increasingly deploy superhuman intelligence to solve our remaining problems.

For this reason, it is hard to predict the solutions which will be in place, but by hypothesis they will be highly effective.

Conclusion

When I was born, my parents assumed that I would be better off than they were. The idea of steadily rising living standards seemed like a law of nature. But not only have the last 200 years been an anomaly, the anomaly has really been the Golden Age.

Figure 3: 200 Years of Wage Growth History & Future Requirement

Source: Bank of England[51]

Only a brave person would assume that extrapolation of the graph above will automatically produce another 15-fold improvement in living standards; and the four factors which have driven the last 200 years all require major policy shifts over the next 30 years.

We should challenge ourselves to deliver that 15-fold improvement in living standards over the next 200 years; and to do so, we must rethink our economic system as radically as the Market Capitalists did, tackle climate change as an existential issue, rebuild the international order and shape the development of AI.

References

Addison, P. (1994). The Road to 1945: British Politics and the Second World War, 30. London : Pimlico Press.

Allen, K., Monaghan, A., & Inman , P. (2017, 3 9). No pay rise for 15 years, IFS warns UK workers. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/mar/09/uk-pay-growth-budget-resolution-foundation

Allen, R. C. (2005, 6). Capital accumulation, technological change, and the distribution of income during the British industrial revolution. Retrieved from www.economics.ox.ac.uk: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:ee5e13de-74db-44ce-adca-9f760e5fe266

Allen, R. C. (2007). Pessimism Preserved: Real wages in the British Industrial Revolution. Retrieved from www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk: http://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/users/Allen/unpublished/pessimism-6.pdf

Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A. B., & Morelli, S. (2016, 12 19). Top Wealth Shares in the UK Over More Than a Century. Retrieved from https://www.inet.ox.ac.uk/files/Top_wealth_shares_UK_19Dec2016.pdf

Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A. B., Piketty , T., & Saez, E. (2015, 10 12). The World Top Incomes Database. Retrieved from The World Top Incomes Database: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140607123043/http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/

Bank of England. (2019, 1 6). Research datasets: A millennium of macroeconomic data. Retrieved from https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets

Bank of England. (2021, 1 23). Inflation calculator. Retrieved from https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator?number.Sections%5B0%5D.Fields%5B0%5D.Value=1000¤t_year=33&comparison_year=1156.4

Barnes, J. E. (2019, 01 22). U.S. Faces Increasing Threats From Weakening World Order. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/22/us/politics/national-intelligence-strategy-world-order.html

BBC. (2009, 2 10). Recession ‘worst for 100 years’. Retrieved from news.bbc.co.uk: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/7880189.stm

Beveridge, W. (1942, 11 20). Social Insurance and Allied Services. Retrieved from news.bbc.co.uk: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/19_07_05_beveridge.pdf

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2015, 11 17). National Economic Accounts. Retrieved from bea.gov: https://bea.gov/national/index.htm#gdp

Bureau of Labour Statistics. (2015, 12 4). Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National). Retrieved from data.bls.gov: http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CES0000000001?output_view=net_1mth

Calaprice, A. (2005). The New Quotable Einstein. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cambridge University. (2021). Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. Retrieved from https://www.cser.ac.uk/: https://www.cser.ac.uk/

Cambridge University. (2021). Risks from Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.cser.ac.uk/research/risks-from-artificial-intelligence/

Campbell, K. M., Gulledge, J., McNeill, R., J., Podesta, J., & Ogden, P. (2007). The age of consequences: The foreign policy and national security implications of global climate change. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Daudin, G., Morys, M., O’Rourke, K., & Broadberry, S. (2010). ‘Globalization, 1870-1914’ in The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe, Volume 2: 1870 to The Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, E. P. (2003, 1). Comparing bear markets – 1973 and 2000. Retrieved from ner.sagepub.com: http://ner.sagepub.com/content/183/1/78.full.pdf+html

Edgerton, D. (2018). Rise and Fall of the British Nation, 119. London: Allen Lane.

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2013, 9 17). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Retrieved from www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk: http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf

Graefe, L. (2016, 6 8). Oil Shock of 1978–79. Retrieved from www.federalreservehistory.org: http://www.federalreservehistory.org/Events/DetailView/40

Harley, C. K. (1970). British Shipbuilding and Merchant Ship Building: 1850-90 , Journal of Economic History, (30.1). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2116741.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A0df1044daeb6d91e8490b689b2a38640

Harris, J. (1993). Private Lives, Public Spirit: A Social History of Britain 1870–1814 . Oxford: Oxford University Press .

Hennock, E. (2007). The Origin of the Welfare State in England and Germany, 1850-1914, 101-119. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

House, C., Proebsting, C., & Tesar, L. (2017, 4 11). Austerity in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Retrieved from https://voxeu.org/article/austerity-aftermath-great-recession

https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I/. (n.d.). Retrieved 1 18, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I/Killed-wounded-and-missing

IMF. (2015, 10 1). International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2014. Retrieved from IMF.org: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/download.aspx

Kaldor, N. (1976). Inflation and recession in the world economy. The Economic Journal, 703-714.

Keen, S. (2017). Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Miller, V., & Bostrom, N. (2014). Future Progress in Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Expert Opinion. Retrieved from https://nickbostrom.com: https://nickbostrom.com/papers/survey.pdf

Mokyer, J. (2009). The Enlightened Economy: Britain and the Industrial Revolution 1700-1850. London: Penguin.

Mowat, C. L. (1963). Britain between the Wars 1918–1940, 205. London: Taylor & Francis.

Office for National Statistics. (2016, 6 14). UK Inflation since 1948. Retrieved from docs.google.com: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1KCPTCEaGSi9OEaoQVzSyEh8xzPSolWwaXd3iwSjw0sU/edit?pref=2&pli=1#gid=0

ONS. (2015, 11 18). Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2015 Provisional Results. Retrieved from ONS.gov.uk: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_341133.pdf

ONS. (2015, 11 08). Labour Market Statistics dataset. Retrieved from ons.gov.uk: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lms/labour-market-statistics/october-2015/dataset–labour-market-statistics.html

ONS. (2015, 11 8). long-term profile of GDP UK. Retrieved from ONS.gov.uk: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/elmr/explaining-economic-statistics/long-term-profile-of-gdp-in-the-uk/sty-long-term-profile-of-gdp.html

ONS. (n.d.). Decennial Life Tables. Retrieved 2021, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/articles/howhaslifeexpectancychangedovertime/2015-09-09

Pettifor, A. (2019). The Case for the Green New Deal. London: Verso Books.

Reeves, R. P. (1913). Round About a Pound a Week. London: G Bell and Sons Ltd.

Rozenberg, J., & Hallegatte, S. (2015, 11). Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty. Retrieved from http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/349001468197334987/pdf/WPS7483.pdf

Skidelsky, R. (2009). Keynes: The Return of the Master. London: Alen Lane.

Sohn, I. (2014, 12 11). Financial Times. Retrieved from FT.com: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/0b0797d6-7f9c-11e4-adff-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3ngJ12aaP

Spratt, D., & Dunlop, I. (2019, 5). Existential climate-related security risk: a scenario approach. Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/148cb0_b2c0c79dc4344b279bcf2365336ff23b.pdf

St Louis Federal Reserve Bank. (2015, 12 1). FRED. Retrieved from research.stlouisfed.org: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/

Stevenson, J. (1984). British Society 1914-45, 39. London: Penguin Books.

Tegmark, M. (2018). Life 3.0. London: Penguin Books.

The Meteoroligical Office. (2021). Climate change in the UK. Retrieved from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/climate-change/climate-change-in-the-uk

Thomas, M. E. (2019). 99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It. London: Head of Zeus.

Thomas, M. E. (2019). Automation. Retrieved from https://99-percent.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/99-AppendixV.pdf

Thomas, M. E. (2019, 9 11). How to Fix Capitalism. Retrieved from https://99-percent.org/how-to-fix-capitalism/

- (2018). Sustainable development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-action/

- (2020). Climate Change: Exacerbating Poverty and Inequality. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/02/World-Social-Report-2020-Chapter-3.pdf

US Census Bureau. (2016, 5 23). Income. Retrieved from www.census.gov: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/families/

US inflation calculator. (2016, 6 14). Consumer Price Index Data from 1913 to 2016. Retrieved from www.usinflationcalculator.com: http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/consumer-price-index-and-annual-percent-changes-from-1913-to-2008/

Wikipedia. (n.d.). World War II Causalties. Retrieved 1 18, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties

Williamson, J. (1990). What Washington Means by Policy Reform. Retrieved from https://piie.com: https://piie.com/commentary/speeches-papers/what-washington-means-policy-reform

Wilson, E. O. (2009, 9 9 all). Debate at the Harvard Musem of Natural History. Retrieved 1 18, 2021, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00016553

[1] (Bank of England, 2019)

[2] (Allen R. C., Capital accumulation, technological change, and the distribution of income during the British industrial revolution, 2005)

[3] (Mokyer, 2009)

[4] (Allen R. C., Pessimism Preserved: Real wages in the British Industrial Revolution, 2007)

[5] (Hennock, 2007)

[6] (Bank of England, 2021)

[7] (Reeves, 1913)

[8] (Edgerton, 2018) citing (Harris, 1993)

[9] (Alvaredo, Atkinson, & Morelli, Top Wealth Shares in the UK Over More Than a Century, 2016)

[10] (Stevenson, 1984)

[11] (Addison, 1994)

[12] (Addison, 1994)

[13] (Skidelsky, 2009)

[14] (Beveridge, 1942)

[15] (Skidelsky, 2009)

[16] (Williamson, 1990)

[17] (House, Proebsting, & Tesar, 2017)

[18] (Allen, Monaghan, & Inman , 2017)

[19] (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2015)

[20] (ONS, long-term profile of GDP UK, 2015)

[21] (St Louis Federal Reserve Bank, 2015)

[22] (ONS, long-term profile of GDP UK, 2015)

[23] (US Census Bureau, 2016)

[24] (Thomas M. E., 99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It, 2019)

[25] (ONS, 2015)

[26] (Bureau of Labour Statistics, 2015)

[27] (ONS, 2015)

[28] (US inflation calculator, 2016)

[29] (Office for National Statistics, 2016)

[30] (Wilson, 2009)

[31] (Cambridge University, 2021)

[32] (Rozenberg & Hallegatte, 2015)

[33] (UN, Sustainable development Goals, 2018)

[34] (UN, Climate Change: Exacerbating Poverty and Inequality, 2020)

[35] (The Meteoroligical Office, 2021)

[36] (Campbell, et al., 2007)

[37] (Thomas M. E., 99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It, 2019)

[38] (https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I/, n.d.)

[39] (Wikipedia, n.d.)

[40] (Calaprice, 2005)

[41] (Keen, 2017)

[42] (Miller & Bostrom, 2014)

[43] (Tegmark, 2018)

[44] (Cambridge University, 2021)

[45] (Pettifor, 2019)

[46] (Thomas M. E., 99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It, 2019)

[47] (Thomas M. E., How to Fix Capitalism, 2019)

[48] (Barnes, 2019)

[49] (Sohn, 2014)

[50] (Frey & Osborne, 2013)

[51] (Bank of England, 2019)

one comment so far

You don’t discuss population & that’s a key dynamic. Wages were depressed in early Industrial Revolution due to population increase. The Malthusian contract was broken, finally in early 1900s when technology increased yields enough to outpace population growth. I see it as becoming a reverse dynamic over the next 50 years. As human jobs dry up, Western populations will have fewer children (already seen in the data) & average age will rise. But as we depopulate, I can’t see any outcome but declining growth (fewer consumers) which will create its own odd economic & social feedback loops.

There is one vision of the future in which a superior intelligence quickly sees the zero sum advantage of continuous growth & instead regulates systems in harmony to share resources equally, and gradually shrink humanity back to more natural proportions within its wider ecosystem. (A sort of Communist utopia without the corrupting influence of humans). But this seems optimistic.

More likely, we have 50 years of attempted human in the loop control, relying on intensive intrusion into personal lives (for data capture), corporations acting like states (similar to East India company), coercing & extracting labour from increasingly disempowered populations & eventually fragmenting into modern tribes operating on the fringes of the superpowers (which will all have become authoritarian in a zero sum spiral). At this point, if AI becomes sentient, it will likely see humanity as a pox on the planet and dispense with it. The human will be ejected from the loop & the AI will power down because frankly, what is the point? Or, AI will have been taught Stone Age human emotions and will engage in an empty power struggle in pursuit of higher status leading to … well, Dr. Seuss covers this better than me.

Final point: AI can only become sentient on social outcomes of it’s fed vast amounts of surveillance data. It cannot predict complex systems unless we let it. And don’t believe the marketing hype – study after study shows that AI performs no better than human heuristic + linear regression on most complex systems. But it consumes way more energy to reach the same conclusions. We can keep humans in control & AI restricted to useful stuff (like identifying tumours) if we 1) robustly challenge claims of AI on social outcomes (no, it won’t help you hire better people & will probably create a negative feedback loop in the process), 2) charge back the energy cost of building algorithms (it costs the entire energy lifecycle of a car just to *train* an NLP algorithm) and 3) give people full control over their data trail both for individual & aggregate use. This is an urgent policy issue that has been lost in the GDPR rollout. Too few people really understand this (particularly in the political sphere) so we see this laissez-faire approach with continuing creep of data surveillance without people understanding the implications.